Born February 1818

Born February 1818

Birthplace Near Easton, MD

Died February 20, 1895

Grave Site Mt. Hope Cemetery, Rochester, NY

Contribution A leader in regional and national suffrage organizations.

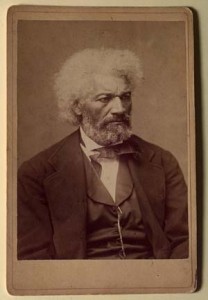

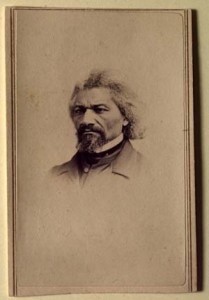

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey (or Baily), later known as Frederick Douglass, was born in February 1818* near Easton, Maryland. He was the son of Harriet Bailey, a slave. Captain Aaron Anthony claimed ownership of Douglass. (It is believed that Captain Aaron Anthony was not related to Susan B. Anthony.)

Douglass spent his early childhood in a cabin with his grandmother Betsey. His mother was hired out and he only saw her on rare visits. In 1824, Douglass was separated from his grandmother and taken to live on the large plantation of Colonel Edward Lloyd, where Captain Aaron Anthony worked. In 1826, he was sent to Baltimore, Maryland to live with Hugh and Sophia Auld, in-laws of Lucretia Anthony Auld, Captain Anthony’s daughter.

Douglass lived in Baltimore from 1826 until 1833, where his first job as a child was to look after the Aulds’ son, Tommy. While he was in Baltimore, Douglass learned to read and write. He was taught by Sophia Auld until her husband forbade it. After that, Douglass taught himself in secret.

Once he had learned to read, Douglass read newspapers and learned about the debate over slavery. He also attended the free African-American churches in Baltimore. At the age of 12 or 13, Douglass bought his own copy of The Columbian Orator, a popular nineteenth-century book on rhetoric. He studied the book, went through the exercises, and taught himself public speaking.

In 1833, Douglass was taken from Baltimore and brought to St. Michael’s, Maryland by his master, Thomas Auld (son-in-law to Captain Anthony, who was now deceased). While there, Douglass organized secret schools for slaves and refused to submit to whipping. One of the schools was broken up by a mob, and he was hired out to farmers known as “slave breakers,” who sought to control his rebellious activities. Yet he continued to defy his slave status. In 1836, he planned to escape but was caught, imprisoned, and eventually sent back to Thomas Auld.

After his failed escape attempt and imprisonment, Douglass was sent back by Auld to Baltimore. There, he was hired out to a local shipyard to learn the trade of a caulker. He joined an improvement society of free black caulkers and attempted, unsuccessfully, to buy his own freedom. In 1837, he met Anna Murray, a free African-American woman.

After his failed escape attempt and imprisonment, Douglass was sent back by Auld to Baltimore. There, he was hired out to a local shipyard to learn the trade of a caulker. He joined an improvement society of free black caulkers and attempted, unsuccessfully, to buy his own freedom. In 1837, he met Anna Murray, a free African-American woman.

In September 1838, Douglass escaped from slavery. He first went to New York City. There, he sent for Murray to join him, and they were married. The Douglasses were to have five children in the next eleven years: Rosetta (b. 1839), Lewis Henry (b. 1840), Frederick Jr. (b. 1842), Charles Remond (b. 1844) and Annie (b. 1849).

In 1838, the Douglasses settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where Douglass found work as a caulker for whaling ships. It was at that time that he dropped the name “Bailey,” in order to protect himself from slave catchers, and became known as Frederick Douglass.

While in New Bedford, Douglass began to read the Liberator, William Garrison’s abolitionist journal. He also attended anti-slavery meetings held in African-American churches. At these meetings he occasionally told of his experiences.

In 1841, Douglass spoke about his slave experiences at a convention of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society held on Nantucket Island. He impressed prominent abolitionist leaders, including Garrison, and was hired as an anti-slavery lecturing agent. Douglass moved his family to Lynn, Massachusetts, and spent the next few years giving hundreds of anti-slavery speeches. In 1843, he joined a group of anti-slavery lecturers on a “One Hundred Conventions” tour, a grueling schedule of stops that included upstate New York, Ohio, Indiana, and western Pennsylvania.

Douglass supplemented his abolitionist speaking activities with the publication of his autobiography in 1845. The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself, was an instant success, and eventually sold over 30,000 copies in the United States and Britain. It was translated into French, German and Dutch. However, Douglass had jeopardized his freedom by putting the details of his life into print. He was forced to flee to Europe to avoid capture and the possibility of return to slavery. He left the United States in August 1845 and embarked on a lecture tour of England, Scotland and Ireland. During the lecture tour, which lasted 20 months, anti-slavery advocates in England raised funds and negotiated the purchase of his freedom. While there, Douglass also raised the funds necessary to start his own anti-slavery newspaper upon his return to the United States.

On October 28, 1847, Frederick Douglass wrote to his close friend, Amy Post, a Rochester, New York abolitionist, “I have finally decided on publishing the North Star in Rochester and to make that city my future home.” The first issue was published on December 3, 1847. By February 1848, Douglass began to move his family to Rochester.

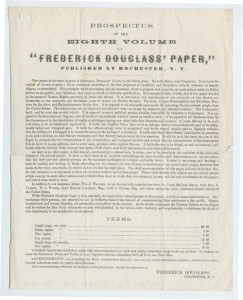

Douglass’s publishing career was to span almost three decades. In 1851, he merged the North Star with another journal, The Liberty Party Paper, and formed Frederick Douglass’ Paper. In January 1859, in addition to the Frederick Douglass’ Paper (FDP), he began to publish another journal, Douglass’ Monthly (which had been originally produced as a supplement to FDP). He stopped publishing Douglass’ Monthly during the Civil War, but in 1870 he purchased 50% interest in the Washington, D.C. paper the New Era. In September of that year the first issue of the New National Era was published.

Frederick Douglass was first and foremost an abolitionist and civil rights activist. Fighting against his own slavery from his earliest youth, he continued to fight against the institution of slavery until its abolition. He spoke and lectured widely for the cause throughout the 1840s and 1850s. In 1849, 1850 and 1851, he organized his own series of lectures in Rochester. He wrote a novella entitled The Heroic Slave, an abolitionist work of fiction published in 1852 in Autographs for Freedom. The Autographs for Freedom was sold as a fundraiser for anti-slavery activities.

In addition to advocating abolition in his lectures and in his publications, Douglass became active in the Underground Railroad, and was instrumental in shepherding many fugitive slaves to Canada. Although he ultimately disapproved of John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry — he believed it was doomed to failure — Douglass had initially assisted in raising funds for Brown’s abolitionist activities. Douglass’ connection to Brown got him in trouble with the law. He was forced to escape to Canada in October 1859 to avoid the possibility of repercussions in the heated atmosphere following the raid. He was assisted in his escape by Amy and Isaac Post, dear friends and fellow anti-slavery advocates.

Douglass sailed from Canada to England in November 1859, lecturing against slavery there. His return to Rochester was spurred by the tragic death of his youngest daughter Annie, on March 13, 1860.

During the Civil War, Douglass asked Lincoln to make abolition a goal and fought for the right of African-Americans to enlist in the Union Army. Upon the success of the latter, Douglass helped to recruit African-American soldiers and wrote a popular editorial entitled “Men of Color, To Arms,” which became a recruiting poster.

After the war, Douglass continued to fight tirelessly for African-Americans’ right to full legal equality, backed by the power of the ballot. He supported passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, and lectured widely for their adoption. In later years, he would speak out against the increased lynchings of African-Americans.

Douglass’ also advocated the rights of women. He participated in the first Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls in 1848 and signed the Declaration of Sentiments. Elizabeth Cady Stanton later reported that the resolution calling for women’s suffrage was passed by that Convention to a great extent through Douglass’ efforts on its behalf. After the convention, Douglass published a positive editorial on “The Rights of Women,” which appeared in the July 28, 1848 edition of the North Star. The History of Woman Suffrage notes that during the subsequent adjourned Women’s Rights Convention held in Rochester on August 2, 1848, “Frederick Douglass, William C. Nell, and William C. Bloss advocated the emancipation of women from all the artificial disabilities, imposed by false customs, creeds, and codes.” In 1853, Douglass signed “The Just and Equal Rights of Women,” a call and resolutions for the Woman’s Rights State Convention held in Rochester on November 30 and December 1, 1853. He also attended and spoke at that meeting.

During the years before the Civil War, Douglass was a close friend of Susan B. Anthony and her family, and often visited the Anthony home. He delivered a eulogy upon the death of Anthony’s father Daniel in November 1862. However, during the years from 1865 to 1870, Douglass split from many women’s rights activists over the issue of passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Anthony and Stanton refused to support the Fifteenth Amendment because it excluded women. Douglass, on the other hand, believed with many abolitionists that it was important to secure the rights of African-American males before working to achieve the rights of women. Their argument was both public and private, and there was resentment and hurt on both sides.

During the years before the Civil War, Douglass was a close friend of Susan B. Anthony and her family, and often visited the Anthony home. He delivered a eulogy upon the death of Anthony’s father Daniel in November 1862. However, during the years from 1865 to 1870, Douglass split from many women’s rights activists over the issue of passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Anthony and Stanton refused to support the Fifteenth Amendment because it excluded women. Douglass, on the other hand, believed with many abolitionists that it was important to secure the rights of African-American males before working to achieve the rights of women. Their argument was both public and private, and there was resentment and hurt on both sides.

Immediately after the adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, Douglass resumed his women’s rights activities. He called for an amendment giving women the right to vote, and wrote an editorial supporting women’s suffrage entitled “Women and The Ballot,” published in October 1870.

In 1872, Douglass’ Rochester home was destroyed by fire, and he moved to Washington, D.C. The New National Era, of which he was part owner, was published in Washington, D.C. In 1874, publication of the New National Era was discontinued. In that same year, Douglass presided over the doomed Freedman’s Savings Bank, a federally-chartered institution created to help former slaves. When Douglass took over the bank was already failing and it declared bankruptcy within months after he assumed the presidency.

During his tenure in Washington, D.C., Douglass also held a number of government posts. From 1877 to 1881, he served as U.S. Marshall for the District of Columbia under the administration of President Hayes. He was appointed the District of Columbia’s Recorder of Deeds by President Garfield, and served in that post from 1881 to 1886. He was the U.S. Minister to Haiti under President Harrison, and served in this post from 1889 to 1891.

During these years, Douglass’ support of women’s rights continued. He attended the 30th anniversary celebration of the first Women’s Rights Convention, held by the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in Rochester in 1878. He also attended the 1881 NWSA meeting held in Washington, D.C. Several of the women present at this convention were welcomed at his home. Douglass was also present at the International Council of Women, held in 1888; there he was introduced to the audience by Susan B. Anthony as a women’s rights pioneer.

Douglass’s wife Anna died in 1882. In 1884, he married Helen Pitts, a feminist from Honeoye, New York. Pitts was a graduate of Mount Holyoke Seminary. While living in Washington, D.C. before her marriage, she had worked on a radical feminist publication called the Alpha. Frederick and Helen Pitts Douglass faced a storm of controversy as a result of their marriage. Douglass himself wrote:

No man, perhaps, had ever more offended popular prejudice than I had then lately done. I had married a wife. People who had remained silent over the unlawful relations of white slave masters with their colored slave women loudly condemned me for marrying a wife a few shades lighter than myself. They would have had no objection to my marrying a person much darker in complexion than myself, but to marry one much lighter, and of the complexion of my father rather than of that of my mother, was, in the popular eye, a shocking offense, and one for which I was to be ostracized by white and black alike. (Douglass, Life and Times… p. 534.)

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, however, remained a loyal defender. She congratulated the two and wrote:

In defense of the right to…marry whom we please — we might quote some of the basic principles of our government [and] suggest that in some things individual rights to tastes should control….If a good man from Maryland sees fit to marry a disenfranchised woman from New York, there should be no legal impediments to the union.

Douglass, in turn, remained faithful to the cause of women’s rights. In fact, he attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. on February 20, 1895, the day he died. During that meeting, he was brought to the platform and given a standing ovation by the audience. He died shortly after he returned home.Photograph of Frederick Douglass gravestone

Douglass, in turn, remained faithful to the cause of women’s rights. In fact, he attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. on February 20, 1895, the day he died. During that meeting, he was brought to the platform and given a standing ovation by the audience. He died shortly after he returned home.Photograph of Frederick Douglass gravestone

Stanton and Douglass had been pioneers in the women’s movement since its inception in 1848. At his funeral, Susan B. Anthony gave a eulogy that Stanton had written. Douglass was buried in Mt. Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

* Douglass himself thought that he had been born in 1817. McFeeley states, “Douglass had calculated that he had been born in 1817; Auld…said it had been in February 1818; this fact was only verified a century later, when Dickson Preston examined the records of Aaron Anthony’s slaves.(McFeeley, p. 294)

Bibliography of Suggested Books & Articles

- Barry, Kathleen, Susan B. Anthony: A Biography of a Singular Feminist, NY: New York University Press, 1988.

- Douglass, Frederick, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Written By Himself, reprinted from the revised edition of 1892, NY: Collier Books, 1962.

- Garraty, John A. and Mark C. Carnes, eds., American National Biography, NY: Oxford University Press, 1999. Douglass’s biography is written by Roy E. Finkenbine and appears in v. 6, pp. 816-819.

- Harper, Judith E., Susan B. Anthony: A Biographical Companion, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 1998.

- Hewitt, Nancy A., Women’s Activism and Social Change, Rochester, New York, 1822-1872, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984.

- History of Woman Suffrage, vols. I, IV. (Douglass appears throughout the History.) The editorial on “The Rights of Women” which appeared in the North Star on July 28, 1848 is reprinted in History, v. I, pp. 74-75.

- McFeely, William S., Frederick Douglass, NY: W.W. Norton & Co., 1991.

- McKelvey, Blake, “Women’s Rights in Rochester: A Century of Progress,” Rochester History, v. X, Nos. 2 & 3 (July 1948), pp. 1-24.

- University of Rochester Special Collections (Rare Books, Rush Rhees Library). U of R notes that there are approximately 100 letters: “The abolitionist orator and writer lived in Rochester between 1847 and 1872. His correspondents include Amy and Isaac Post, Samuel Drummond Porter, Theodore Tilton, and Jenny Marsh Parker. Of particular interest are two underground railroad passes written by Douglass.”

Bibliography of Suggested Web Sites