Born February 15, 1820

Born February 15, 1820

Birthplace Near Adams, MA

Died March 13, 1906

Grave Site Mt. Hope Cemetery, Rochester, NY

Contribution Worked more than 50 years for women to have the right to vote in the United States.

Quotation “Failure is impossible.”

Related Web Site Susan B. Anthony House

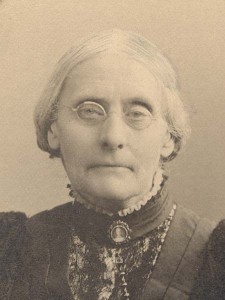

Susan Brownell Anthony was born on a farm near Adams, Massachusetts on February 15, 1820. Her father, Daniel, was a liberal Quaker (Society of Friends) abolitionist (someone who believed that there should be no slavery) and at various times a shopkeeper, the owner and manager of cotton mills, a farmer, and an insurance agent. Her mother, Lucy Read, was a Baptist whose father (Daniel Read) had fought in the American Revolution and served in the Massachusetts legislature. Lucy Read Anthony had six children that survived infancy, four girls and two boys. Anthony was the second child.Photograph of Susan B. Anthony

In 1826, when Anthony was six years old, she moved with her family to a large brick house in Battenville, New York. Battenville is a town in the Hudson Valley region approximately thirty-five miles north of Albany. The house included a store and a schoolroom. There Anthony, along with her brothers, sisters and some neighborhood children, received the bulk of her formal education in a home school established by her father. There, some of her teachers were women.

Before she was sixteen, Anthony started to teach, taking small jobs near her home. However, she began to feel that her own education had not been enough. Her father, who as a Quaker encouraged education in his daughters, enrolled her in Deborah Moulson’s Female Seminary, a Quaker boarding school in Philadelphia, in 1837.

Anthony was not happy at Moulson’s, but she did not have to stay there long. She was forced to end her formal studies because her family, like many others, was financially ruined during the Panic of 1837. Their losses were so great that they were forced to sell everything in an auction — even their most personal belongings — which were saved only when Anthony’s uncle, Joshua Read, stepped up and bid for them at the last minute, in order to restore them to the family.Photograph of Susan B. Anthony

In 1839, the family moved to Hardscrabble (later called Center Falls), New York in the wake of the Panic and economic depression that followed. That same year, Anthony left home to teach and to help pay off her father’s debts. She taught first at Eunice Kenyon’s Friends’ Seminary in New Rochelle, New York and then at the Canajoharie Academy in 1846. There, she rose to become headmistress of the Female Department.

Anthony’s father moved the family once again in 1845, this time to a small farm in Gates, west of Rochester, New York. By 1849, Anthony had grown dissatisfied with teaching, and took up her father’s offer to come to Rochester and run the farm while he built up his insurance business. There, her lifelong career in reform began.

In 1848, Anthony’s younger sister (Mary) attended the Adjourned Convention in Rochester, New York of the first Woman’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls. At the time she was more interested in pursuing temperance reform. (Temperance is the restraint in the use of alcoholic liquors.) Her commitment to temperance came in part as a result of her Quaker upbringing. She never did officially leave the Quaker meeting, although at this time she also began attending the liberal Unitarian Church.

Anthony joined the Daughters of Temperance in 1848. A few years later, she was not allowed to speak at a temperance rally in Albany because she was a woman. She left the Society, and shortly thereafter formed the Woman’s New York State Temperance Society.

During the 1850s, Anthony became increasingly interested in women’s rights. In the early 1850s, she met Elizabeth Cady Stanton in Seneca Falls. They were to become lifelong friends. In 1852, she attended her first woman’s rights convention, in Syracuse, New York.

During the same year, she incorporated women’s rights into three other reform movements: temperance, labor and education. She helped to organize the “Whole World’s Temperance Convention” in New York City. (The “World’s Temperance Convention,” held in the same city, had refused to recognize women delegates — or “half” the world, as these women said.) That year, she also helped a group of Rochester, New York seamstresses draft a code outlining fair wages for working women in the city. And, at a New York State Teacher’s Association meeting, also in Rochester, she demanded that women be allowed to participate in discussions formerly opened only to men.

In 1854, Anthony began to organize petition drives for women’s rights, including women’s suffrage. In each county of New York State she, along with others, went door to door obtaining signatures to present to the legislature.

Although she never lapsed in her commitment to women’s rights, as the Civil War approached, Anthony, always an anti-slavery advocate, poured more and more of her energy into working for abolitionists. From 1856 until the Civil War, she was the principal New York agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society. As such, she was constantly speaking to the public, frequently to violent and hostile crowds. When the Civil War broke out, Anthony and Stanton organized the Women’s Loyal National League, which organized petition drives for freedom for slaves and secured hundreds of thousands of signatures in the process.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Anthony and Stanton found themselves increasingly at odds with many of their former reform allies. Many reformers wanted to focus on winning rights — including the right to vote — for newly emancipated African-American men. Their efforts led to the passing of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution. Anthony and Stanton were against these amendments because they included the word “male.” They believed that with the word “male” written in these amendments, it would be even harder for women to obtain the right to vote for women.

At this time, Anthony and Stanton began to concentrate exclusively on women’s rights. By now, Anthony had become a brilliant organizer and political strategist, and she showed a tireless devotion to the cause. In 1868, she and Stanton began to publish a newspaper for women’s rights. Called the Revolution and originating in New York City, the first issue appeared in January. This newspaper championed women’s suffrage, equal pay for equal work, women’s education, the rights of working women and the opening of new occupations for women, as well as the liberalization of divorce laws.

In May of 1869, Anthony and Stanton formed the National Woman Suffrage Association. This organization would focus on securing a federal woman suffrage amendment as well as working on key state campaigns for the vote. Anthony served as a member of the executive committee and later as vice-president, while Stanton was the president. For the next thirty years, Anthony traveled constantly across the country, speaking tirelessly to promote women’s suffrage and women’s rights.Photograph of S. Anthony and E. Sweet

In 1872, Anthony decided to test the constitutionality of the ban on women’s suffrage. She, with many of her sister suffragists, registered to vote in Rochester, New York. She then voted in the presidential election. She was arrested for this act and in 1873 she was tried in the U.S. District Court located in Canandaigua, New York. The trial was a sham — the judge did not even poll the jury before pronouncing her guilty. She was given a fine of $100, which she never paid.

In the late 1870s Anthony, along with Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage, began to undertake the difficult task of writing the massive Image of Anthony’s inscription on History of Woman SuffrageHistory of Woman Suffrage. Anthony did not consider this the most pleasant task she ever faced — she said she would rather make history than write it — but nevertheless the first three volumes were published by 1886. (The History of Woman Suffrage eventually was six volumes long.)

In 1888, Anthony officially extended her scope from a national to a worldwide concern for women’s rights when she founded the International Council of Women. She acted as the head of the U.S. delegation to its meetings in 1899 (London) and 1904 (Berlin).

Anthony’s commitment to women’s education was reinforced at the end of the 19th century by her tireless fundraising to secure the funds necessary to allow for the admission of women to the University of Rochester. The money was finally raised by 1900 and women were admitted, thanks in large part to her efforts.

Photograph of memorial service for S. AnthonyAnthony attended a women’s suffrage convention in Baltimore in February 1906. During the course of that trip she stated her belief that “Failure is Impossible.” She died shortly thereafter of heart failure at her home in Rochester in March of 1906.

Bibliography of Suggested Books & Articles

- Archer, Jules, Breaking Barriers: The Feminist Revolution from Susan B. Anthony to Margaret Sanger to Betty Friedan, (Epoch Biographies) NY: Viking, 1991.

- Barry, Kathleen, Susan B. Anthony: A Biography of a Singular Feminist, NY: New York University Press, 1988.

- DuBois, Ellen Carol, Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America, 1848-1869, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1978.

- Flexner, Eleanor, Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights Movement in the United States, New York: Atheneum, 1968.

- James, Edward T., Janet Wilson James and Payl S. Boyer, eds., Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971. Biography of Susan B. Anthony by Alma Lutz, v. 1, pp. 51-57.

- Sherr, Lynn and Jurate Kazickas, Susan B. Anthony Slept Here: A Guide to American Women’s Landmarks, NY: Random House, c1976, 1994.

- Ward, Geoffrey C., Not For Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, (based on a documentary film by Ken Burns and Paul Barnes), NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999.