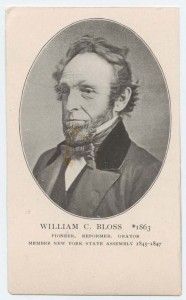

Born January 19, 1795

Born January 19, 1795

Birthplace West Stockbridge, MA

Died April 18, 1863

Grave Site Brighton Cemetery, Brighton, NY

Contribution Abolitionist, reformer and New York State legislator

William Clough Bloss was born on January 19, 1795, in West Stockbridge, Massachusetts. His parents, Joseph and Amy Wentworth Kennedy Bloss, were farmers. His father was a veteran of the American Revolution.

The Bloss family moved to the town of Brighton, New York in 1816. He taught in Maryland and South Carolina at some point between 1816 and 1823, when he joined his family permanently in Brighton. That year, he built a tavern on the Erie Canal and married Mary Bangs Blossom. The couple had six children.

Bloss, a Methodist, became an early advocate of temperance (abstinence from alcoholic liquors). In 1826, he poured the contents of his bar into the Erie Canal and gave up his tavern. In 1830, he sold the building and moved to nearby Rochester.

Bloss was also a supporter of the Anti-Masonic movement. The Anti-Masons were a party formed during the 1820s to fight what people perceived to be the corruption and overwhelming political and economic power held by the Masons. Anti-Masonic feeling in Rochester was crystallized by the disappearance of William Morgan, a disgruntled Mason who had written an anti-Masonic tract. When his tract came out, Morgan was harassed, arrested, and jailed. When he was released from jail, he was quickly kidnapped (with the assistance of Masons) and never heard from again. The ensuing uproar led to the formation of Anti-Masonic groups in the area. Bloss was a delegate to the Monroe County Anti-Masonic convention in 1829.

During the 1830s, Bloss became involved in the anti-slavery movement. In the summer of 1833, he signed a call for the first New York Anti-Slavery Convention in Utica, New York. During that same year, he and other anti-slavery advocates worked with Thomas James, an African-American minister, to organize a local anti-slavery society. According to James, the first of three meetings scheduled for this purpose was held in the courthouse and attracted a large crowd of the curious. At the second meeting, onlookers asked numerous questions, and at “the third they drowned with their noise the voices of the speakers and …turned out the lights.” At this point Bloss, whom James describes as “not a man to be cowed by opposition,” got a meeting room for the group in the Third Presbyterian church. There, under the protection of locked doors, the harassed advocates organized the society.

In 1834, after local papers refused to publish the society’s constitution and bylaws, Bloss and other leaders started their own bi-weekly paper, The Rights of Man. Bloss and James acted as agents for this newspaper.

Bloss continued his activities on behalf of African-Americans in the 1840s. His home on East Avenue (between Stillson and Chestnut Streets, where the Cutler Building now stands) was a stop on the Underground Railroad, providing shelter for escaped slaves. In 1844, Bloss, a Whig, won a seat in the New York assembly, where he served three one-year terms. (The political party called the Whig Party in the U.S. favored a loose interpretation on the Constitution.) As a legislator, he attempted to amend the state constitution in order to end discrimination in voting rights for “people of color.” He also promoted the Free School Law, which called for an end to legalized segregation in public education. In 1849, after his stint in the assembly, he fought to admit African-American children to regular district schools in Rochester. Frederick Douglass, who moved to Rochester in 1847, wrote that “[f]rom the first I was cheered on and supported in my demands for equal rights by such respectable citizens as…Bloss,” among others.

Bloss continued his activities on behalf of African-Americans in the 1840s. His home on East Avenue (between Stillson and Chestnut Streets, where the Cutler Building now stands) was a stop on the Underground Railroad, providing shelter for escaped slaves. In 1844, Bloss, a Whig, won a seat in the New York assembly, where he served three one-year terms. (The political party called the Whig Party in the U.S. favored a loose interpretation on the Constitution.) As a legislator, he attempted to amend the state constitution in order to end discrimination in voting rights for “people of color.” He also promoted the Free School Law, which called for an end to legalized segregation in public education. In 1849, after his stint in the assembly, he fought to admit African-American children to regular district schools in Rochester. Frederick Douglass, who moved to Rochester in 1847, wrote that “[f]rom the first I was cheered on and supported in my demands for equal rights by such respectable citizens as…Bloss,” among others.

During the 1850s, Bloss raised funds to arm anti-slavery settlers in Kansas, which was at that time a literal battleground in the fight to end slavery. In 1854, he traveled to Worcester, Massachusetts to meet a group of these would-be settlers as they headed out West. Upon their arrival in Worcester he presented them with Bibles that were inscribed “To Establish Civil and Religious Liberty in Kansas.”

Bloss was also an early advocate of women’s rights. His son has said that he endorsed the idea of women’s suffrage as early as 1838. At the August 2, 1848 Adjourned Convention held at the Unitarian Church in Rochester, Bloss spoke out to support the Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions. The History of Woman Suffrage records that, along with William C. Nell and Frederick Douglass, Bloss “advocated the emancipation of women from all the artificial disabilities, imposed by false customs, creeds, and codes.”

Bloss promoted a number of other reforms throughout his life. When convicted murderer Ira Stout wrote a plea asking that the death penalty be abolished, Bloss agreed and joined a protest against capital punishment. The protest, held at Rochester’s City Hall on October 7, 1858, included Susan B. Anthony, Amy Post and Frederick Douglass, as well as Bloss and others. The protesters were forced to disperse and escape through the back of the hall when a hostile mob invaded the premises and the police were unable to maintain order. Stout was later executed.

Bloss promoted a number of other reforms throughout his life. When convicted murderer Ira Stout wrote a plea asking that the death penalty be abolished, Bloss agreed and joined a protest against capital punishment. The protest, held at Rochester’s City Hall on October 7, 1858, included Susan B. Anthony, Amy Post and Frederick Douglass, as well as Bloss and others. The protesters were forced to disperse and escape through the back of the hall when a hostile mob invaded the premises and the police were unable to maintain order. Stout was later executed.

During the 1850s, Bloss opposed the American Party (or “Know Nothings”), a party that appealed to anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic elements and which, in 1855, made a strong showing in Rochester municipal elections.

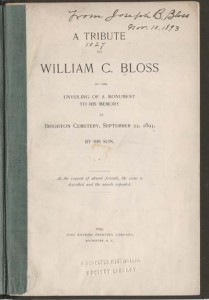

William Clough Bloss died on April 18, 1863. There is a monument to his memory in the Brighton Cemetery. He was also memorialized by a club that bore his name.

Bibliography of Suggested Books & Articles

- Douglass, Frederick, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself, NY: Collier, 1961 (reprint from revised ed. of 1892)

- Garraty, John A. and Mark C. Carnes, eds., American National Biography, (multiples vols.), NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 1999. v. 3, pp. 54-55. Biography by John D. French.

- Hewitt, Nancy A., Women’s Activism and Social Change: Rochester, New York, 1822-1872, Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1984. (Bloss mentioned in conjunction with trial and protests concerning Mr. Stout.)

- James, Thomas, “The Autobiography of Rev. Thomas James,” Rochester History, Vol. XXXVII, No. 4, (October 1975).

- Johnson, Paul E., A Shopkeeper’s Millennium: Society and Revivals in Rochester, New York, 1815-1837 NY: Hill and Wang, 1978. Although this work does not mention Bloss by name, it gives a good description of the Anti-Masonic movement in Rochester, NY.

- McKelvey, Blake, “A History of the Police of Rochester, New York,” Rochester History, Vol. XXV, No. 4 (Oct. 1963) (Bloss mentioned in conjunction with protests concerning Mr. Stout.)

- McKelvey, Blake, “Lights and Shadows in Local Negro History,” Rochester History, Vol. XXI, No. 4, (Oct. 1959).

- McKelvey, Blake, “Women’s Rights in Rochester: A Century of Progress,” Rochester History, Vol. X, Nos. 2 & 3, (July 1948)

- Perkins, Dexter, “Rochester One Hundred Years Ago,” Rochester History, Vol. 1, No. 3 (July 1939)

- Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds., History of Woman Suffrage, 2d ed., Rochester NY, Charles Mann, 1889 (c1881) (reprint, Source Book Press, 1970) vol. I, p. 76.

Bibliography of Suggested Web Sites