Born December 20, 1802

Born December 20, 1802

Birthplace Jericho, NY (Long Island)

Died January 29, 1889

Grave Site Mt. Hope Cemetery, Rochester, New York

Contribution Anti-slavery and woman’s rights advocate

Amy Kirby was born in Jericho, New York on December 20, 1802. Her parents, Joseph Kirby and Mary Seaman Kirby, were farmers and she was one of eight children. The Kirby family belonged to the Society of Friends (Quakers).

When Amy Kirby was in her early 20s, she moved to Scipio, New York to live with her sister, Hannah Kirby Post, and brother-in-law, Isaac Post. Hannah died in 1827, and Amy Kirby married Isaac Post in 1828. In addition to the two children Isaac Post had with his previous wife Hannah, Isaac and Amy (Post) has four children of their own: Jacob, Joseph, Matilda, and Willet. Only four of the children live to be adults (Mary – the daughter of Isaac and Hannah, Jacob, Joseph, and Willet).

In 1836, the Posts moved from Scipio to Rochester, New York, to a house at 36 Sophia Street (now North Plymouth Avenue). That same year, Post’s younger sister Sarah also moved to Rochester. A few years later, in 1839, Isaac Post started a drugstore — named Post, Coleman and Willis — in the Smith Arcade, at 4 Exchange Street in Rochester.

Amy Post became active in the anti-slavery movement in Rochester soon after she arrived in the city. She signed a petition against slavery in 1837, and her home, a busy station on the Underground Railroad, sometimes housed between ten and twenty fugitive slaves per night. A host of anti-slavery lecturers also stayed with her when they came to Rochester to speak. These guests included William Lloyd Garrison, William C. Nell, Abby Kelley, and Frederick Douglass.

Amy Post became active in the anti-slavery movement in Rochester soon after she arrived in the city. She signed a petition against slavery in 1837, and her home, a busy station on the Underground Railroad, sometimes housed between ten and twenty fugitive slaves per night. A host of anti-slavery lecturers also stayed with her when they came to Rochester to speak. These guests included William Lloyd Garrison, William C. Nell, Abby Kelley, and Frederick Douglass.

Post helped to found the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society (WNYASS) in 1842, and throughout the 1840s was active in organizing and holding a series of anti-slavery fairs in order to raise money and sympathy for the cause. In 1844, she was selected to be the WNYASS delegate to the annual meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society in New York City and in 1852, when the Society held its annual meeting in Rochester, she served on the business committee. In 1853, with Lucy Coleman, she attended a Western Anti-Slavery Society meeting and went to Canada to visit fugitive slave communities.

In 1845, Post stopped attending the Rochester Monthly Meeting of the Society of Friends and left Genesee Yearly Meeting (Quakers). She left the Quakers because she disagreed that the Society’s ministers and elders had the right to judge the actions that individual members took in matters of conscience, such as abolitionism, the belief that there should be no slavery. (Although Quakers thought slavery was sinful, many ministers and elders disapproved of the methods used by radical anti-slavery reformers and looked in disfavor upon their own members who agreed with these methods.)

Because of her work in the anti-slavery movement, Post developed friendships and shared correspondence with many famous anti-slavery advocates. One such friendship was with Harriet Jacobs, an escaped slave. Jacobs stayed with the Posts for almost a year while she was in Rochester, and Post encouraged her to write her autobiography. Jacobs published Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl in 1861. Lydia Maria Child wrote its introduction, and Post, under an assumed named (alias or pseudonym), wrote the postscript.

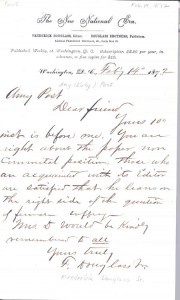

During the Civil War, Post tapped into her vast regional anti-slavery network in order to collect goods including food, clothing and medical supplies for the newly freed slaves. She ensured that these were distributed by working with the agent for the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society (LASS) in Virginia.Image of letter to Post from Anthony

Post worked for woman’s rights as well as for the abolition of slavery, and was involved in the woman’s rights movement from its inception in 1848. In July of that year, she traveled nearly fifty miles to the Woman’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls. There, she participated in debates and signed the Declaration of Sentiments. When the participants in that meeting decided to hold another convention in Rochester two weeks hence, Post agreed to work on the arrangements committee. She, with other members of the committee, shocked even women’s rights advocates Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott by insisting that a woman (Abigail Bush) be chosen to preside at this Adjourned Convention. At this convention, which took place on August 2, 1848, Post called the meeting to order and again participated in discussion and debates regarding the Declaration of Sentiments.

Two weeks after the Rochester Convention, Post joined forces with two seamstresses to form the Working Women’s Protective Union. The object of this group was to work toward wage increases for working girls. Post became the treasurer of the Union.

Post attended numerous women’s rights conventions throughout her life. At a Woman’s Rights State Convention held in Rochester in 1853, she signed a call and resolutions entitled “The Just and Equal Rights of Women.” After the Civil War, she joined the Equal Rights Association and the National Woman Suffrage Association. In 1872, the year her husband Isaac died, she was one of the women who along with Susan B. Anthony attempted to vote in the national election. Unlike Anthony, Post was not allowed to vote, although she did succeed in registering. In 1873, Post once again attempted to vote, but was again turned away.

Post attended numerous women’s rights conventions throughout her life. At a Woman’s Rights State Convention held in Rochester in 1853, she signed a call and resolutions entitled “The Just and Equal Rights of Women.” After the Civil War, she joined the Equal Rights Association and the National Woman Suffrage Association. In 1872, the year her husband Isaac died, she was one of the women who along with Susan B. Anthony attempted to vote in the national election. Unlike Anthony, Post was not allowed to vote, although she did succeed in registering. In 1873, Post once again attempted to vote, but was again turned away.

When the National Woman Suffrage Association held its convention in Rochester, New York on July 19, 1878 to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention, Post again helped with arrangements and served as one of the delegates from Monroe County. She was one of the founding members of the Women’s Political Club, (later named the Political Equality Club) founded in Rochester in 1885. In 1888, well into her eighties, she attended the International Council of Women in Washington, DC, which was billed as the largest women’s rights convention held up until that time.

Besides suffrage and abolition, Post was also involved in a number of other causes throughout her life including Spiritualism and temperance.Photograph of Amy Post grave

Besides suffrage and abolition, Post was also involved in a number of other causes throughout her life including Spiritualism and temperance.Photograph of Amy Post grave

In 1882, the Rochester community showed its appreciation and respect for Post’s work with a celebration of her 80th birthday. She died seven years later, on January 29, 1889, and her funeral was held at the Unitarian Society.

Bibliography of Suggested Books & Articles

- Anthony, Susan B et al., History of Woman Suffrage, Rochester, NY: Charles Mann and Susan B. Anthony, 1881 and 1889. vols. I, II, III, IV

- Coleman, Lucy, Reminiscences, Buffalo: H.L. Green, 1891 (A paper on Post read by Colemen before the Woman’s Political Club of Rochester, NY, appears on pp. 83- 86.

- Garraty, John A. and Mark C. Carnes, eds., American National Biography, NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 1999. v. 17, pp. 724-725

- Hewitt, Nancy A., Women’s Activisim and Social Change: Rochester, New York, 1822- 1872, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984. (The bulk of the biographical information (especially about Post’s life in Rochester) came from this source.)

- Isaac and Amy Post: Early Rochester Activists, Rochester: 1985 (videocassette, 6 min.)

- McKelvey, Blake, “Civic Medals Awarded Posthumously, Rochester History, Vol. XXII, No. 2, April, 1960.

- McKelvey, Blake, “Woman’s Rights in Rochester: A Century of Progress,” Rochester History, Vol. X, Nos. 2 & 3, July 1948.

- Yellin, Jean Fagan, Written By Herself: Harriet Jacobs’ Slave Narrative, (Offprint from American Literature, v. 53, no. 3, Nov. 1981)

Bibliography of Suggested Web Sites